It’s funny how wedded we Christians are to groups, tribes and movements. I suppose it is how most people make sense of their Christian identity in a broadly secular culture: by aligning with a movement, a denomination, or a group. So I guess I shouldn’t be surprised that when I wrote about leaving one church and experiencing another that some thought I was talking about “leaving fundamentalism” and “joining the Reformed”. Actually, that’s not at all what happened, nor what I meant. I was really taking about revivalism.

First, some definitions. Fundamentalism, as an idea, is entirely biblical. It is the idea that Christianity has some fundamental or essential doctrines. Christianity has a set of truths which cannot be denied and still survive as Christianity. To teach that the essentials are essential — that the fundamentals are fundamental — makes you a believer in the idea of fundamentalism. The idea has been held by many who would eschew the title fundamentalist, such as J. Gresham Machen, who wrote about it in his book Christianity and Liberalism.

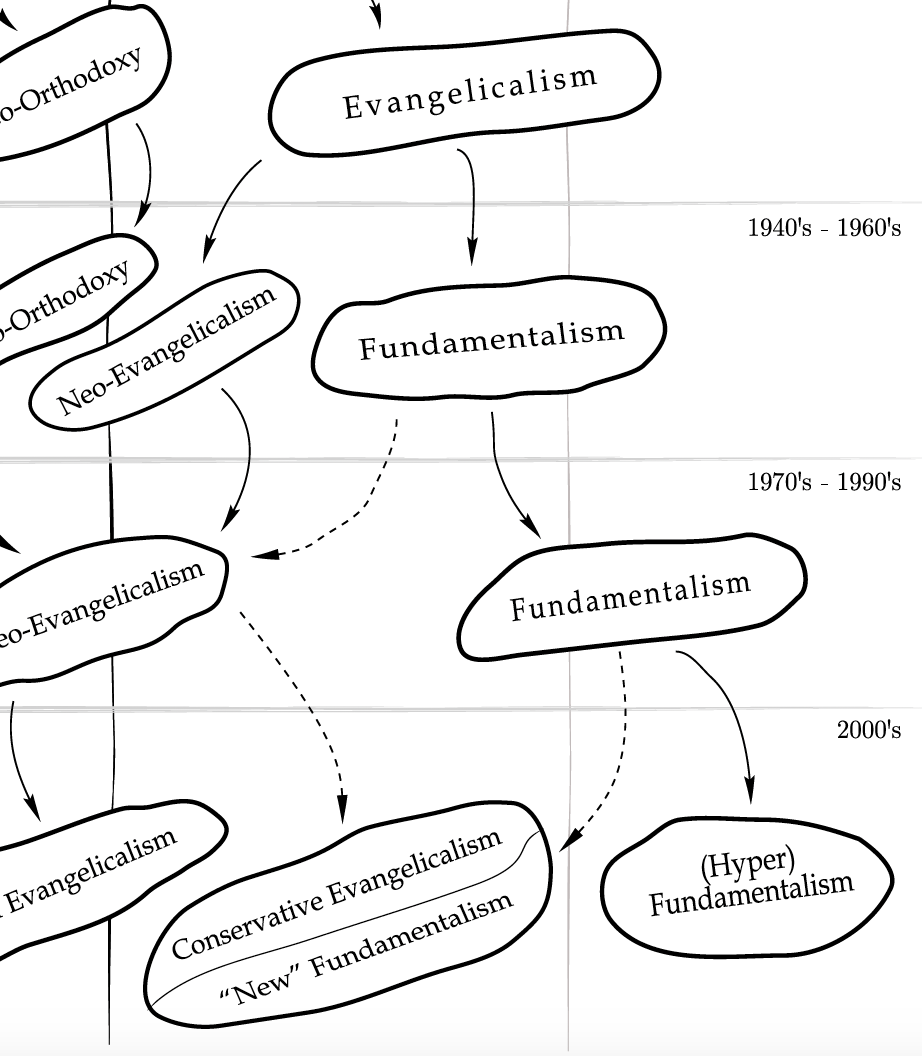

Fundamentalism as a movement, or group, refers to those Christians who reacted to the perceived compromise of evangelicals in the 1940s and 50s who were partnering with people who denied the fundamentals. For example, Billy Graham himself professed the fundamentals, but partnered with people who didn’t in his 1957 New York crusade – so fundamentalists felt the need to separate from his ministry. Fundamentalism as a movement spawned churches, Bible colleges, universities, seminaries, radio stations, publishing houses, youth ministries, camp ministries, and so forth. From the early 2000s, a rapprochement occurred between the conservative wing of evangelicals and the moderate wing of fundamentalism, while the extreme left wing of evangelicalism and extreme right wing of fundamentalism have continued veering in their respective directions. Fundamentalism as a movement, like any movement, has the good, the bad, and the ugly. Most people know only the bad and the ugly: rabid King-James Onlyism, obscure taboos, insular tribalism, pugnacity, and anti-intellectualism. But I’ll venture to say that the bad and the ugly in fundamentalism were largely the fault of revivalism.

Revivalism has its roots mainly in the Second Great Awakening, and particularly in the techniques and success of Charles Finney. Finney (1792-1875) represents a turning point in Christianity.

Finney came to reject central parts of the Westminster Confession of Faith, including the idea that humans have original sin. He also rejected the idea that God must sovereignly draw sinners to salvation. He believed that given the right circumstances, right atmosphere, and right techniques, anyone could be brought to repentance or experience revival. Therefore, he set about to create circumstances that would, in his words, ‘produce religious excitements’. Finney’s standard for judging if something were appropriate to use in this regard was very simple: its effectiveness.

Finney was wildly successful. Hundreds of thousands were ‘converted’, and his meetings were considered mass revivals. Historians doubt how permanent the conversions of Finney’s revivals were; at any rate, they were nothing like the Awakenings of Jonathan Edwards and George Whitefield. However, the church could not ignore Finney. Most were enamoured of his success. Thus, revivalism was born.

For revivalism, ministry was determined by outward results. Increased numbers, and growing attendance figures became the yardstick of success. Further, revivalism’s techniques to achieve these results became increasingly pragmatic. The ends not only justified the means, they demanded them. Once results by any means was an acceptable, unquestioned modus operandi, mass appeal became part of ministry. Populism was in its DNA. Revivalism increasingly looked to the world for its methods – using the music, songs, emotional manipulation and sensual stimulation that unbelieving marketers had successfully used for decades. Put simply, churches that embraced revivalism shifted gears from biblical worship to worldly amusement, from biblical ministry to worldly marketing.

Revivalism is steeped in hyper-Arminianism. As a doctrine, method, and ministry philosophy, everyone should reject revivalism. (Note well: we should not eschew revival itself, which is a worthy goal when understood as a true awakening of the lost to salvation and of the saved to consecration.) The doctrine and practice of Finneyesque revivalism hollows out ministries, trivialises worship and preaching, and generally destroys stability or maturity in churches.

Moreover, revivalism should not be confused with fundamentalism per se. Revivalism affected (and infected) all groups: evangelicals, fundamentalists, Pentecostals, and others. Plenty of fundamentalists, however, did not, and do not, accept revivalism. Nor should Calvinism be seen as the panacea to every problem revivalism produces. Calvinism probably clashes swords with revivalism a lot sooner than conservative Arminianism does, which is why an ex-revivalist finds the emphases in Reformed churches so refreshing.

But as for me, I still have my fundamentalist card. I embrace and teach the idea of fundamentalism. I’m indebted to and thankful for the best of the movement, which taught me invaluable distinctives: a caution towards culture, the case for separation, theological dogmatism, and the importance of missions. I was educated in a fundamentalist seminary. The church I pastor was birthed out of fundamentalist missions. No one really uses the moniker fundamentalist on their churches anymore, but I’m happy to own my heritage, rightly defined.

What I’ve left behind is revivalism. Man-centred, pragmatic, manipulative ministry practices and philosophies never should have entered or remained in gospel-teaching churches. I unhesitatingly shake the dust of revivalism off my feet, and call others to do the same.

I tend to agree with Don regarding Revivalism not being a movement. It appears to be more of a technique, particularly in the context of late 20th century church-growthism, whereby pews and pulpits were expunged in favor of comfy chairs and a stage that elicited the ambiance of a rock concert, with the speaker ambling about being humorous, relevant and glib. As you might glean, not my cup of tea.

Regarding categories to which you refer in the article, groups, tribes and movements, I’m pretty ignorant. Finneyism seems to be a well-intentioned technique, but hardly one that could be deemed heretical. I’m familiar with the term “Reformed” but I don’t know what they are reformed from, but had thought they were pretty darn fundamental, so when you make a distinction, one to the other, it leaves me confused. Also, If someone held a gun to my head and demanded that I explain the difference between Arminianism and hyper-Arminianism with the wrong answer being a death sentence, the result would be ugly and it would be messy. I guess this is my way of asking if all these categories are all that important. I don’t see ‘em in the Bible. I also don’t see anything about Philadelphia-ism. Or Laodicea-ism. Seems like they would be better categories to focus on, since those distinctions would seemingly matter more to God.

There is a movement, the Keswick movement, that spawned the revivalism that crossed over to the United States. And I see the most massive iteration of pragmatism arise from revivalism. The impurity of all this relates to something bigger than the Keswick movement, I believe, mainly out of a line of apostasy from Roman Catholicism, which branched out into many different ungodly forks.

I wonder if Revivalism is as monolithic as you describe. In other words, the way you describe it, Revivalism equals Finneyism (which I am happy to label as heretical). But I wonder if that is an adequate description. The way I see it, most of the faithful Christians who produced evangelicalism/fundamentalism were influenced by Revivalism, and I have a hard time labelling them as Finneyism. True, some of them were too enamoured with Finney’s methods but they remained faithful to the gospel itself.

I guess I am saying that I don’t see Revivalism as a movement as such. Not like Fundamentalism or Evangelicalism

Anyway, all the best to you. You know I appreciate you and your ministry

Don Johnson

Jer 33.3

AMEN!

Comments are closed.